10.28.2013

What it Really Means to be a Real Man

Men are getting a lot of shallow advice about how to be men, and a lot of it is coming from the church.

Avoid passivity!

Embrace accountability!

Take charge! Bring your family to church! Bring your wife flowers! Just do it! Do active things followed by lots of exclamation points!!!

Does anybody else feel like Brick Tamland might be behind this whole thing?

What’s empty about all the “just do it” challenges that men are receiving is that they’re all about trying harder to control what is spinning out of control. Control your temptations! Control your anger! The problem is that control is rooted in fear, and fear will not lead us into freedom.

We fear failure.

We fear getting it wrong and being wrong.

We fear that we’re defective.

We fear appearing soft and weak.

We fear being afraid!

We fear criticism, especially from our wives.

We fear that our version of what it means to be a man is not the version of what it really means to be a man.

So we flail around, trying to control whatever we can, only to panic when we still fail, still get criticized, and still get it wrong.

(Thank you, Brene Brown, for chapter 3 of Daring Greatly, which helped to form that list).

The truth is that most of us need to release the grip on control, so that we can get at the root of our fear, which is shame.

What we need are flawed men who begin to tell their raw stories of losing control. We need to hear about how they’re naming and moving through their pain and loss (death), and how they’re embracing a radical grace that is setting them free (life). This kind of courage will slowly eradicate the culture of shame in men.

I’ll never forget the time when Dave Busby (a pastor who died of cystic fibrosis almost twenty years ago) told a huge room full of men and women that he had recently watched porn in a hotel room on a ministry road trip.

He talked about the process of feeling empty, then bored. He talked about making the decision to turn it on, then watching it for the next thirty minutes. He talked about the even deeper emptiness and the pit of deep shame into which he tumbled afterwards. Then he talked about the phone call he made to his best friend in the middle of the night, to whom he laid it all out. He talked about the process of losing control and what he did about it. He talked about what happened when he named it out loud to someone else. He talked about the grace that he received.

I’ll never, ever forget that.

Men need to hear that they will feel empty, and that they shouldn’t try hard to avoid feeling empty. The question is: What you will do when you inevitably do feel empty? How you will respond when you’ve done something stupid because you felt so empty? Can we hear some stories of normal men who get empty?

Now, if you’re a pastor and that is your story, please don’t stand up in your congregation on Sunday and tell them about your porn addiction. That wouldn’t be a good first step. But tell someone. Tell someone about how close you are to doing something stupid. Tell someone about how angry or bored or frustrated you are.

We are afraid of telling the truth about what’s really happening in our lives because we have a long history of hiding what’s really happening, and talking about what really isn’t happening.

“So how many girls have you guys slept with?”

This was the question that the tall, good-looking senior guy threw out in the locker room during the winter of my sophomore year of high school.

We all shifted uneasily and a few of us mumbled some very tentative responses. One of us finally asked him how many girls he had slept with. He thought hard about it, obviously working out some really advanced mathematics.

“About a hundred,” he finally answered.

We all sat there, stunned. It didn’t occur to me until years later that he might have been lying. Isn’t it interesting that of the millions of things that happened to me in high school, I have a vivid memory of this very short, seemingly insignificant scene?

Fast forward to every pastor’s conference I’ve ever attended. The same question gets asked, every time: “So how many people come to your church?”

We need to see that this question is actually the same question that tall, good-looking senior asked in that locker room.

So what are men supposed to talk about, and what can we quit talking about?

Can we start with some baseline assumptions?

You’re going to feel empty. You’re going to be attracted to people who are not your spouse sometimes, and it doesn’t mean you’re a terrible husband. You’re going to be bored with your life, and you’re going to be angry about it. You’re going to feel like a failure at work. You’re going to find yourself on the edge of doing stupid things. You’re going to do some stupid things. You’re going to be a bad listener (sometimes) and feel defective about it.

Men who are walking towards maturity are finding ways to talk about those things so that they return to who they are. These men are releasing control and becoming expansive. They are creating wide spaces for others to become who they actually are.

We can quit comparing ourselves to each other, endlessly berating each other, and acting like there is one kind of ideal man. I have a friend who loves to hunt and smoke cigars, and he’s a great man. I also have a friend who loves musicals and baking, and he’s a great man. There are so many ways to be a great man.

Now, a word about men who crash and burn.

Over the past several months, I have heard stories four pastors who have had affairs, lost their jobs, and wrecked their marriages. Each one of them doubtlessly knew that they were supposed to avoid passivity and remain accountable.

They needed something more. We need something more. These men are not monsters. They are good men who just stayed hidden for way too long. They are men who are losing the battle with fear and shame.

Dallas Willard once explained the five-step process that he saw men walk through on their way to destroying their lives. He said that it didn’t matter if it was drugs, alcohol, sex, overworking, or something else; it was always the same journey.

First, they got really busy. Then they get unsettled and restless. Then, they got angry. Then they felt entitled. Then they acted out.

Where are you on that journey?

Can you take the courageous step to tell someone about where you actually are? Then, try to be still long enough to ask this dangerous question: What do you want? When you dig underneath the anger and the entitlement, what do you really want? Who might be able to help you move towards that?

It might take a while to cut through the shame and the fear. It is slow work. But this is the work of becoming a real man. And it is worth it.

I want to be a real man. A flawed, growing, honest, expansive man with an easy smile, who is learning to create wide spaces for the people in my life to become who they actually are.

Source: The Actual Pastor

10.10.2013

I AM

I have a terrible habit of living in the future.

I don’t know why I do it… I just do.

I’m always thinking, worrying and preparing for what’s to come that I end up tying myself into anxious knots.

Then there are the times I’m haunted by my past.

All the regrets, disappointments and frustrations can lead me straight to the trough of depression if I let them.

A few weeks ago, I got stuck being anxious about the future again.

I had a lot on my plate. Nothing crazy, just, you know, a new position at work, some travel to work around, two wonderful kids at home who want to play with their daddy, some weddings and families to photograph, friends, relationships, family… and oh yea… My wife and I are expecting the birth of another child at the beginning of October!

Then, as if nudged by someone, I was reminded of a poem my mother-in-law sent me back in June:

I AM

by Helen Mallicoat

I was regretting the past and fearing the future.

Suddenly my Lord was speaking:

My name is I AM.

When you live in the past,

with its mistakes and regrets,

it is hard. I am not there.

My name is not I Was.

When you live in the future,

with its problems and fears,

it is hard. I am not there.

My name is not I Will Be.

When you live in this moment,

it is not hard. I am here.

My name is I AM.

I was reminded that the only time I’m living my *actual life* is right now, in the present moment.

The past can’t be changed and the future isn’t here yet. And if I’m spending too much time regretting my past, or being anxious about the future, I’m not here.

Tolstoy said it best when he said, “The present is the moment in which the divine nature of life is revealed. Let us respect our present time; God exists in this time.”

The present moment is a gift. It’s the only moment we have control over. It’s the only time we get to choose. It’s the only time we get to be who we really are. It’s the only time we get to be our actual self.

If you’re stuck somewhere in your past, let go. Breathe deep. God is with you.

If you’re anxious about what’s coming, let go. Breathe deep. God is with you.

He is not I Was.

He is not I Will be.

His name is I AM.

Source: The Actual Pastor by Dan Bennett

10.07.2013

There is More

Everyone who has run a marathon insists that the marathon is really two races: the first twenty miles, and the last six point two.

During the first twenty miles, assuming you have adequately trained, your body does what you have prepared it to do: At mile 10, you wonder why you don’t run marathons every day of your life. Thousands of people shout your name, cow bells echo the clarion call of your own personal greatness, endorphins pulse through your body, and the road floats beneath you as you glide through the miles with effortless joy.

At mile fifteen, your legs begin to feel fatigued, but you still enjoy the race. I’ve even had deliriously happy moments at this phase of the race when I felt sad about the inevitable finish line looming in the distance; I didn’t want it to end!

But at mile twenty, it all begins to change. The glycogen in your body is rapidly diminishing. What used to be a slight ache in your hips is now constant and sharp, as if you are missing some essential lubricant, without which you will grind to a halt, in a heap of smoke and bones and pain. The bottoms of your feet, which used to feel fluid and graceful, are now made of iron; they’re heavy and they clang in protest with every foot strike.

If the first twenty miles are mostly physical, the last 6.2 are all mental.

Fans lining the sides of the course, noticing your obvious pain, will shout encouraging banalities like, “You’re almost there!” even though you know you are nowhere near the end. Your mind and your body are now engaged in full-scale war. Your body demands that you quit this foolish, meaningless quest. I have run 10 marathons, and I cannot recall even once when I did not desperately want to quit somewhere between mile 20 and the finish.

In the last two miles of the race, your focus narrows. You feel every stab of pain, your brain is foggy with dehydration, the blister on the back of your heel is now open and raw, and you can’t believe you haven’t seen the mile 25 marker yet. You convince yourself that in your state of semi-delirium, you must have missed it. But something inside you knows you have not.

Mile 25 is a torture chamber. But as you creep by the miler marker, you realize that you are going to finish. Though the pain continues to increase, your mind has conquered, and your body has given in. You know that you are going to finish. I have run one particular marathon 9 times, so I know every step of the route intimately, especially the last 1.2 miles. At mile 26, the runners turn slightly left, crest a gentle hill, and then the finish line comes into view. In that moment, a wash of emotion comes over me that causes me to weep. By some act of exquisite grace on the part of the course planners, these last two tenths of a mile are mostly downhill, and sometimes I draw on the last drips of glycogen that remain in my body and attempt to sprint down that hill and across that mat, signifying that the race has ended, and I have endured.

I do not run for the medals, tee shirts, for accolades from friends, or because I’m addicted to competition. I run marathons because of what is forged in the crucible of those last painful miles of the marathon: when I fear that there is nothing left, there is more.

There is more.

Photo Source

Source: The Actual Pastor

10.03.2013

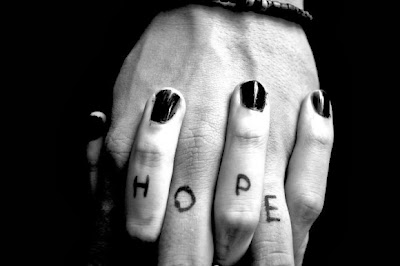

Hope Within Imperfection

Within each of us is a belief that the future holds something bright. This belief can be something that gets us up in the morning. It propels us to keep “moving forward.” We all want to believe is a brighter future. However, there might be something that says to us, that if the future is the place where the light is, what am I living in now?

Within each of us is a desire to “fix” our lives. So we read, “Five steps to a happier you” books. We fall into the latest diet trends. Then, Cosmo tells us 26 new sex positions to obtain the perfect sex life. And, after every book, magazine, exercise, and practice, we come to two conclusions:

I’m tired.

I’m not in control.

I have had the privilege of working with four mentally disabled for the past six years of my life. Some of them have struggles walking because of balance. Some of them struggle with the bathroom. Some of them need help brushing their teeth. They need help with medications, their banking, making food. Life has struggles. They might be able to get slightly more efficient, independent, or capable of doing these things. But, the reality is, life has struggles. And, what the disabled teach us is to surrender and accept our struggles. Sometimes, we can get slightly more efficient, independent, or capable. Sometimes, we just need to accept that we are powerless and we are not in control.

That feeling of being powerless and not in control is an awful one. From an early age, we are taught that in order to be acceptable we are taught that we need to control our behaviors and conform to a certain behavior and image. We are taught to tame and control our behaviors, feelings, actions, and thoughts to fit this ideal. Unfortunately, we can’t be in control all the time. I can’t control everything I do. I can’t control everything everyone else does. And, if the definition of functional is being able to perfectly manage and control my life and outcomes, I am dysfunctional.

The good news is that there is a God who doesn’t expect us to be perfectly functional. The God that we worship says, “Come to me as you are and I’ll love you as you are.” The God that we worship offers us grace. And, grace is the love that heals the wounds of dysfunction. This God says, “I embrace your messiness. I embrace your failure. I embrace your pain. I embrace the parts of you that you feel like are dying inside, because, I will use those places to offer my healing and new life for others.”

While the future may be brighter in the future because we feel like we can control our destiny, hope is mostly found in the loving presence of a God, a friend, a significant other, or whoever allows us to accept the dysfunction inside of us. Hope is someone who loves you in your darkness. Hope is someone who accepts the parts of you that you find unacceptable. In the case of one of my mentally disabled friends (who happens to be 300 pounds), hope looks like allowing me to check him for hemorrhoids and see if I need to apply medication.

Photo Source

Source: The Actual Pastor by Mike Friesen

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)